How fair are public finance decisions for children?

Itir is six years old and lives in Turkana county, north-west Kenya. He was treated for malnutrition at Lodwar County hospital.

This is a lifesaving health service in a region where almost a quarter of children under the age of five are stunted. When Itir got medical help at the hospital, he benefited directly from Kenya’s investments in its health system.

However, public finance decisions – ie, decisions about how much to spend on health care or education or what tax policies to follow – are not impacting children equally. For instance, a child won’t benefit from public investments in healthcare if no government-provided health services are available, or if their family can’t afford potential out-of-pocket costs.

A new research approach allows us to better understand how government decisions on spending and tax policies affect children living in different forms of poverty.

Fair Shares?

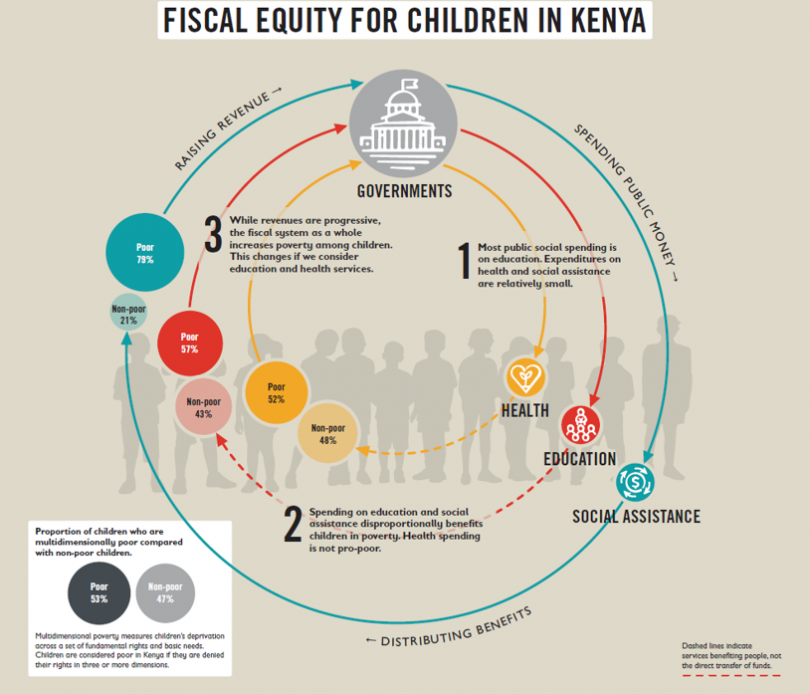

Our new report “Fair Shares? Fiscal Equity for Children in Kenya” puts this approach into practice: by conducting a child-focused fiscal analysis for the first time in Kenya, we find that social spending on children is pro-poor overall. This means that children living in poverty benefit more from public spending on health, education and social protection, than those who are not poor.

This sounds like all is as it should be! However, the first look hides some important differences: for instance, spending on primary education is very progressive (poorer children benefit more than richer children, on average), but this is the opposite for secondary education. A similar picture emerges for health: primary healthcare is progressive, while the much larger investments in hospitals mostly benefit richer children. Social assistance (eg, cash transfers) are very much pro-poor, but small in size.

More worrisome is that if we look at government spending and tax policies combined, we find that financing decisions in Kenya actually increase poverty for families with children. These findings should prompt us to re-think how we can ensure that equity considerations are playing a far more central role in policy discussions – from the planning process and budgeting through to the provision of services.

Behind the scenes

Analyses such as the one in Kenya help us to better understand which groups of children (eg, children living in poor households or in a certain region) are benefiting or are being hurt by public finance decisions. This requires us to bring together two different perspectives:

- We need to understand how much governments spend on social sectors and programmes and how they raise the required revenues. Administrative information (eg, government budgets or tax policies) often provide us with those insights.

- A child can only benefit from spending if they or their families actually use public services. Detailed household surveys (similar to those used in GRID, our Child Inequality Tracker) provide us with those insights.

The methodology which brings both sides together (called the ‘fiscal incidence analysis’) has been around for many years.

However, until recently it has lacked a dedicated focus on children. The results of these new studies provide us with insightful analyses on how public finance decisions (intentionally or unintentionally) impact children living in poverty. This adds an important tool to our public finance toolbox.

Widening the scope

Understanding the impacts of public finance decisions on children impacted by inequality and discrimination is not only important in Kenya, but all over the world.

To help fill this information gap, we are working with partners to bring this analysis to many more countries (Indonesia will be the next with results published soon). Check out the details of this analysis.

Finally, the new SDG indicator 1.b.1 on pro-poor social spending, proposed by Save the Children and UNICEF, offers a welcome backdrop to this work (even if it is not currently focused on children). This indicator requires all countries to report how much their public spending on health, education and social protection benefits poor people in their countries. This means that governments themselves (with the support of international organisations, civil society and academia) need to measure fiscal equity and report it regularly. This will significantly improve transparency and data availability in the future.

Accelerating progress for children

Governments across the world need to scale-up investments in children’s futures, whether to deliver Universal Health Coverage, get children back to school after the pandemic, or provide child-sensitive cash transfer systems. Measuring fiscal equity is an essential part of this journey, to ensure that public investments are having the greatest possible impact on the lives of the children that need them most.